Japan Society Hosts "Dawn of Japanese Animation" Retrospective February 13th-16th in NYC

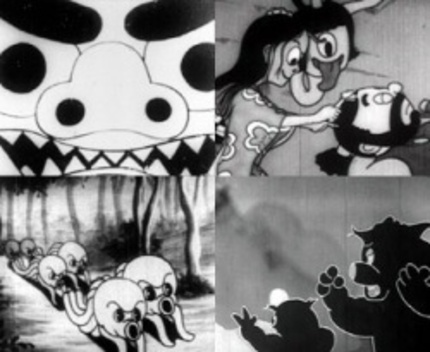

From February 13th-16th, the Japan Society hosts the “Dawn of Japanese Animation” program, a collection of black-and-white cartoons predominantly from the 1930s. The program celebrates the roots of anime as manga eiga or manga films. Each day of the program celebrates a different facet of cartoons loosely based on genres and subgenres. Day one features cartoons from the “Chambara (or: drama involving swordplay and samurai) & Action” genres, followed by “Horror & Comedy,” “Propaganda” and “Music and Dance.” “Chambara” seems a fitting enough place for the program to start considering the cartoons’ roots in shonen, or stories mostly intended for adolescent boys.

While plot is ultimately irrelevant in many of the featured cartoons considering their length and their emphasis on visual gags, the best cartoons in the first night are the cautionary tales and fables that make sense of the real world with the help of talking animals, flying planes and hidden treasure. They teach the difference between right and wrong in ways that the “propaganda” cartoons ape but without the monotonous and largely uninspired formulas that many of the latter conform to. THE BAT relates how the bat became nocturnal while THE PLANE CABBY’S LUCKY DAY shows a pilot’s fortunes change after saves an eagle and is in turn rewarded with a casket of gold coins. The hubris of both people and animals is always repaid in kind unless the guilty are repentant—the eagle in PLANE CABBY is sure that he’s the best dancer of all the eagles and is subsequently punished when two passing hunters shoot him out of the sky. Kids get their fill of mild-mannered indoctrination from both the “action” and the “propaganda” segments, seeing firsthand the rewards of being more gutsy than nimble in TARO’S EARLY TRAINING DAYS or the glories of catching baddies as a hot dog military officer in CORPORAL NORAKURO. Adults get a trip down someone else’s memory lane.

It should go without saying that as with American contemporaries like “Merrie Melodies,” there’s plenty of exaggerated but the bloodshed is never really so grisly that it rob its audience of carefree thrills. Sides split and heads pop off only to come right back on a moment later. The ultra-violence associated with many prominent examples of modern anime, like Otomo’s AKIRA or Oshii’s GHOST IN THE SHELL is absent here and will only seep into the form later on. Like its audience, the form is clearly in its infancy and like the Warner Bros. productions, they’re just as affably goofy.

These are, however, decidedly Japanese cartoons. OVER A DRINK centers on a “vagabond youth” with no money to his name as he gets drunk on sake and dreams of discovering treasure on the bottom of the ocean from a boat guarded by skeleton pirates. If you think you haven’t crossed the cultural rubicon just yet, marvel at how he’s challenged in his dream by two samurai to prove that he’s Japanese but he cannot until he shows them his loach-catching dance. Western elements show up most obviously in the “comedy” cartoons, through the celebration of America’s favorite pastime in OUR BASEBALL MATCH and while the music for both shorts was only added recently, in the use of the main theme from SINGIN’ IN THE RAIN in both BASEBALL and SANKO AND THE OCTOPUS: A FIGHT OVER A FORTUNE.

The institution itself was very much a product of its culture, featuring a live Benshi narrator, providing voices and reading intertitles for all of the cartoons to go along with the cartoons musical accompaniment. The Japan Society has done another great job of assembling a program that loving recreates the atmosphere in which the cartoons were originally featured, bringing to mind the Leonard Maltin hosted “Warner Night at the Movies.” Sadly, I can’t really comment on the live action short films which accompany each of the program’s themed nights except to mention them in passing because while some of them were silent films, it was pretty impossible to understand what was going on without English subtitles (rest assured, there will be subs for the live performances).

It’s impossible to lose sight of the fact that the cartoons of “Dawn” are representative of another time. They’re precursors to anime, the unique cultural icon that has carried all the high and low connotations of its various themes, genres and styles throughout the years. The worst connotations have always been linked to the clichés of adventure series like DRAGON BALL Z and that’s something that remains largely true with the featured entries from early serials. Serials starring heroes like Sankichi the monkey, Momotaro, Taro and Hatanosuke are all fine but, with little exception, lack spontaneity thanks to their formulaic cookie cutter scenarios. What they lack story-wise they make up for in terms of production values, taking full advantage of the financial support that some of the other non-institutionalized cartoons seem to lack—which might be why they’re in better shape than others. While the quality of the characters’ animation may look amateurish in comparison to the elaborate backdrops in a “horror” cartoon like DANEMON’S MONSTER HUNT IN SHOJOJI, there is no such discrepancy in TARO’S MONSTER HUNT.

What allows these cartoons—and later anime—to rise above the traditional but woefully accurate stereotype of the inferiority of the generic serial character are the cartoonists whose voices emerge from within such restricting settings. Yasuji Murata did several seemingly independent projects like THE BAT as well as both of the featured Momotaro cartoons, while Noburo Ofuji did several of the best featured musical cartoons as well as THE NATIONAL ANTHEM KIMIGAYO, the most memorable of the “propaganda” cartoons—if for no other reason than the fact that it’s the most austere of the bunch. Some of the labels of the themes may seem a bit misleading—“propaganda” mistakenly brought to mind images of un-PC caricatures and heavy-handed political statements while the “horror” cartoons are just “action” with some skeletons and a few pesky shape-changing raccoon-dog yokai, or folk creatures—but the program is holistically exactly what it seems like otherwise. Showcasing both exemplary individual’s achievements in the medium as well as giving an idea of what else was out there—which so few cultural film program manage to do without excluding some comparatively lower quality but important popular entries—DAWN offers up a bit of the marginalized past in an attempt to ground what came later.

By seeking to give anime a definable starting point, it gives what many curious but ultimately clueless Westerners crave, namely borders that clearly show an observable progression to the seemingly limitless medium of today. It’s also a great way to regress and enjoy the simple pleasures of an antiquated but nonetheless vibrant collection of curios.

For more information on DAWN OF JAPANESE ANIMATION, go here.