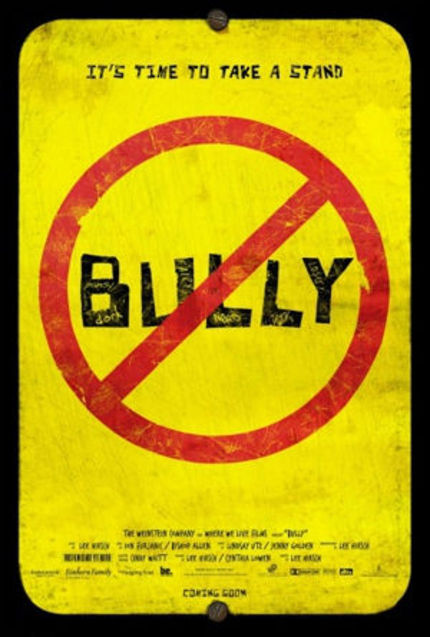

Review: BULLY Provokes Discussion More Than It Provides Substance

Bully will potentially go down in history as the film that finally made America's MPAA explode into tiny little pieces, its relevance called into question due to its insistence, even after appeal, that a documentary film that tries to portray the social morass of bullying uses one too many dirty words and is condemned to a Restricted rating that would make it challenging to find the very youth audience it's directed at. [Thus, the Weinstein Co. decided to release it unrated in the U.S.]

It may be a cynical ploy for publicity, but at its heart the Weinsteins' fight for the film to be shown in unaltered form is a noble one. In a land where violence is allowed but sexual language is taboo, the sheer stupidity of the entire system is called into question by the way this film is being treated, and it may very well lead to either a complete rethink or an abandonment of previous reliance on the ratings scheme all together.

So, other than outcries about ratings stupidity, does the film itself have anything interesting to say?

Short answer, kinda. In the meantime, I'm going to talk about me, the way any narcissistic film review should.

It'll come as no surprise that as an esteemed, internationally praised online-based film journalist that I had my fair share of bullying as a kid. Hell, I grew up a Jew in a land of white bread and mayo North of the big city, where everyone mildly ethnic went to the local Catholic school. (We have two public systems here in Canada, it's weird, but that's beside the point). Growing up, I had pennies thrown at me in the hallways, Swastikas written on my locker, and was subject of more than enough humiliation for several lifetimes. For years I was dunked every morning and afternoon into the social petri dish that is the yellow school bus, a 45 minute schlepp each way across town to attend so-called "gifted" classes. Segregated from a gen pop of normal students at that school except during the chaos of recess, I was short, bespectacled, and considered weird by nature; eating stupid looking crackers every Passover didn't help. Kids were kids, and they were sometimes brutal.

Two things come to mind looking back on this. Not only did I have issues being picked on both on the bus and on the playground, but I have almost completely sublimated my own culpability, my own doucheyness towards others that I too reveled in picking on. I remember making fun of some funny-looking girl until it made her cry. I remember getting into tussling matches with people even smaller than me. I was bullied, but, upon reflection, I also bullied others, something that in much more palatable ways still continues to this day. I was like the victim much more than I remember being the victimizer, but I'd be lying to myself if I wasn't the cause of a lot of pain for quite a few people.

In other words, except in extreme situations, the catch-all term "bully" is an enormously complicated one. It's certainly extremely easy to call for the end of all extreme or excessive child-on-child violence, be it physical or psychological, but that's like calling for increased literacy (are there really people against such things?). The devil's in the details, when you get beyond the more obvious, extreme examples into the everyday behaviour of children within a social environment, and its apparent increase in both intensity and frequency makes it certainly ripe for serious investigation.

Which brings us to the film: It's fair to say that Bully is a pretty movie, shot quite well by director Lee Hirsch using quite a lovely colour palate and small digital cameras that bring the intimacy of its central characters to the screen in an extremely compelling way. It's a movie that tries to make you feel appropriately aggravated, and for most it will communicate the idea that there's something concrete that can be done to end what's presented as a curable epidemic.

Which brings us to the film: It's fair to say that Bully is a pretty movie, shot quite well by director Lee Hirsch using quite a lovely colour palate and small digital cameras that bring the intimacy of its central characters to the screen in an extremely compelling way. It's a movie that tries to make you feel appropriately aggravated, and for most it will communicate the idea that there's something concrete that can be done to end what's presented as a curable epidemic.

Bully will give you a sense that you're seeing real insight into some truly horrifying examples of child brutality, seeing an inept school system ill-equipped to deal with even the most superficial of cases and dozens of suicides resulting, we're told, from incessant bullying. It's trying to do that classic thing of giving voice to the voiceless, providing the stories of the downtrodden, or those left in the wake of the consequences of these reprehensible behaviours.

What the film dances around is that the behaviour of bullying in all but the most extreme cases is so complicated, so often fraught with competing challenges, that can only be solved through mechanisms beyond the scope of anything explored in depth in this film. At times, it feels as if the film's simple message almost belittles (inadvertently, of course) the real-world concerns that underlie these situations.

In the most cut-and-dry of cases, we see a young, awkward boy being pummeled on a bus, the footage shocking and raw, the bus driver seemingly oblivious to the goings on. As the footage plays and the violence escalates, we're left to wonder how long this will continue without at least the filmmaker stepping in, before a title card tells us that after a period of time they did just that, and initiate a series of meetings with school administrators.

These moments are heartbreaking, but feel strange, as if we're seeing something both intimate and self-consciously cinematic at the same time. These aren't hidden cameras, there's obviously adults on the bus shooting this mayhem over a period of time, and yet it seems to go on unchecked until the heroic filmmakers step in to snitch on the goings on.

Other stories are brought in to try and show a bit of the range of the subject - we see a young lesbian girl who's finding her way in her Bible Belt town, and her father coming to terms with his changed feelings due to having a gay child. We meet several parents coming to terms with the suicide of their children, a death that they ascribe to bullying circumstances that don't get delved into in detail.

There's the young African American girl who brought a gun onto a bus because she herself was bullied, waving it around on grainy security footage, the wide-eyed terror of her busmates chilling. We meet her in a detention center as her mom visits, and there's never talk of how she got the gun, about the culpability of the parents, about any of those that she terrified as a way of lashing out. When the girl is released from psychiatric evaluation, we follow her home, with no insight of what her life reintegrating back into a society of her peers is like.

This is indicative of much of the film as a whole; we're granted smatterings of interesting stories, but given little depth to any of them. For example, we don't have any footage inside the schools of the young gay girl, we hear nothing from those on the bus that were victims of this "fighting back". The film tries so very hard to give a semblance of balance, yet when you pick at a single thread it all collapses into a heap.

No single film can truly address the complex situation that Bully delves into, and I do not fault it for falling far from the mark of its lofty goals. As a point of departure for discussion, I think it may prove to be valuable. That said, there are moments where what we don't see is extremely telling, where we don't get to hear from those doing the bullying (or their parents), when we don't here from many voices within the school system that may be actually effectual in ways that no school personnel appear to be throughout.

Basically, when the film slides towards the actual procedures that would contribute to the curbing or even elimination of bullying within the school environment, it fails pretty miserably. The work slips into kneejerk sentimentality, with a protracted ending complete with lofted balloons and candlelight vigils that are fine for commemoration but near useless when it comes to dealing in a protracted, adult way with the situation.

It's hard not to feel yourself like a bully when addressing the film's many shortcomings, so earnest is its message and presentation, but it's entirely for the reason that one can clearly see the vital need for a work to truly address the changing threat that kids are facing that makes this all the more disappointing. Notions of cyber bullying (certainly a growing concern) are barely discussed, and no one seems to address what appears to be a horrifying escalation in the tenor of physical abuse. We're wondering why the hell doesn't the bus driver turn around, even once, to see what appears to be a kind of mob attack in the seats right behind her. These are fundamental concerns that the film seems almost reticent to address, sticking instead to the mostly black-and-white, victims vs. victimized narrative, fit for easy consumption and glossing over the heart of the matter.

It's hard not to feel yourself like a bully when addressing the film's many shortcomings, so earnest is its message and presentation, but it's entirely for the reason that one can clearly see the vital need for a work to truly address the changing threat that kids are facing that makes this all the more disappointing. Notions of cyber bullying (certainly a growing concern) are barely discussed, and no one seems to address what appears to be a horrifying escalation in the tenor of physical abuse. We're wondering why the hell doesn't the bus driver turn around, even once, to see what appears to be a kind of mob attack in the seats right behind her. These are fundamental concerns that the film seems almost reticent to address, sticking instead to the mostly black-and-white, victims vs. victimized narrative, fit for easy consumption and glossing over the heart of the matter.

I would adore if a more mature documentary outfit like PBS's Frontline would have dealt with the same individuals, as the access they get and the tales told by the families is at times astonishing. Alas, Bully at times feels like an infomercial, an advertisement for a given cause more than a serious documentary. It comes across as a kind of tease for a more serious examination of these issues.

Those that made parts of my early life miserable helped make me who I am today, my scars both physical and mental partly key to my character as an adult. That said, I never once had to undergo the kind of brutality that some of these kids on film have to live through, and you can't help but want to do something to make a difference. I credit the filmmakers for finding a way to at least begin addressing these concerns in an accessible fashion, and remain amused that this ratings flap should, in fact, drive more to see the work. With the film's success, hopefully that will lead into far better works that genuinely tackle the issues at the heart of the film.

In the end there's much to admire about Bully, but I think with a little less idealistic or strident tone, a little more concerted effort to really explore one of the key stories in even greater, nuanced detail, and the refocusing of much of its part-manipulative, part-moving final act, we'd be left with a hell of a film.

Bully opens in New York and Los Angeles on Friday, March 30, before expanding in limited release in the U.S. and Canada the following week.