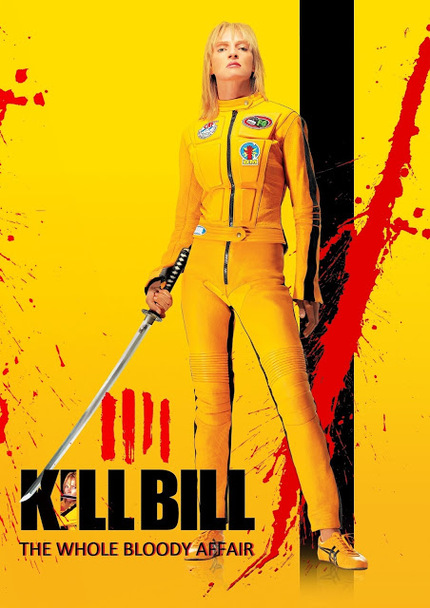

10+ Years Later: KILL BILL Represents Peak Tarantino

All of Tarantino’s work has an air of overt respect for filmmaking.

I think that’s why we let him get away with such cinematic bombasity (and cruelty) - because everything he does seems to so sincerely honor the legacy of cinema, in all its regional and aesthetic diversity, even as he utterly reinvents much of it.

This convergence of reverence and creativity - a symbiosis that defines him as an auteur - is nowhere more concentrated and original than in Kill Bill. As he has aged he’s matured, and with experience he has developed in all facets of his film-making, but returning to Kill Bill after a long break, with the hindsight of all his subsequent work, it’s clear to me that Kill Bill is something special.

Kill Bill shouldn't work. It's a mess of tones that veer wildly, styles that rarely share the same film, and genres within genres. And yet, this never seems to cost the film any momentum or continuity; it's a 4.5-hr spectacle that follows it's own logic as it ricochets through the kaleidoscope of Tarantino's cinematic mind.

I think some of the joy many of us take in Tarantino’s existence stems from a sense that he embodies a quintessential paradox experienced by cinephiles everywhere - the contradictory and unquenchable thirst for originality and familiarity; creation of the possible and mastery of the proven. We return to films and genre’s we love, and we take pleasure in revisiting familiar characters and places, but we also crave films that we could never imagine, and vicarious experiences of the utterly novel. Tarantino gets it, perhaps more than any living director, because he lives it, and in his desire to quench his own thirst he slakes ours, at least for a while.

I've come to consider Kill Bill the love letter to film. Take a look at this partial list of seventy films referenced in the two volumes. Now, could we be finding what we’re looking for, rather than what was placed there? Perhaps, but that distinction also misses the whole point of Tarantino.

Though his films are laced with references they don't strike me as especially overt. Instead, they come pre-digested; they are now part of his being, and emerge inextricably blended with his own creativity. Edgar Wright is another master of homage, but his touch feels more intentionally self-aware, hence the comedic edge. Wright winks at us in the hopes we'll catch the joke, whereas Tarantino seems to simply metabolize the creative calories he has consumed, allowing them to manifest mostly without fanfare.

Perhaps the most complimentary analogy I can personally make in this regard, is to suggest that Tarantino is to film what Tolkien is to language; a sub-creator so immersed in the medium he loves that he simply exudes the wellspring from which he has always drunk. Kill Bill is Tarantino's Quenya.

Since rewatching Kill Bill I have noticed other ways he simultaneously reveres and reinvents, such as in his casting choices. Tarantino is of course well known for using iconic actors in roles that often subvert their own oeuvre, but it was this time that I really began to notice how he will leverage associations we bring to enrich our experience of these new roles.

Sonny Chiba, of course, springs to mind. Few have spilt more cinematic blood, and yet Tarantino’s act of homage - casting Chiba as Hattori Hanzō - is to elevate him to a pacifistic sage of sorts; a character who has transcended his legacy of violence as a swordsmith. In so doing, Tarantino has provided a role for Chiba that similrly acknowledges his legend is something that transcends his particular association with violent cinema.

I want to talk a little bit about the legacy of Kill Bill in the context of cinematic violence, and I’d be interested to hear from readers whether any of this resonates with you. I should pre-empt this by saying that the release of Kill Bill in 2003 about represents the time that I took up film consumption as a way of life.

I have more or less split my time since between keeping up with what’s current and catching up on what I missed. Consequently, my experience of the trajectory of violence in cinema is rather like a Tarantino movie itself; bouncing around in time and tone and style. Still, I feel like Kill Bill represents a significant moment in our relationship with film violence, for two reasons.

Firstly, the violence is depicted as poetry. Tarantino presents violence, particularly in Kill Bill, as a form of expressive art. We watch in wonder and awe, not horror, even though what we're seeing is intellectually abhorrent. Instead, it's mesmerizing; physically graceful, visually dazzling, and meticulously executed. Tarantino has transformed an act of moral outrage it into something of aesthetic beauty. No doubt others did this before Tarantino, and Tarantino himself did it before Kill Bill, but in hindsight Kill Bill feels like it changed the game.

Secondly, the film itself seems to transcend its own violent nature. Bill’s eventual death is a non-event. The fight with the film's big bad is no fight at all; it's a philosophical argument for Beatrix Kiddo's existential essence. Is she who Bill says she was born to be - in his metaphor, born to kill, just like Superman was born to be supernatural, and only dresses as Clark Kent to hide his true nature?

Or is she at heart a good person, capable of a normal and peacable life; someone not inherently violent, but who has put on a suit for violence, ala Batman. In this sense, Beatrix seems to represent something of the war within human nature; are we violent and bestial creatures who must willfully deny our animal nature in order to be civilized, or are we innately humane, but with an inherited propensity for violence? In reality, all of the above in all likelihood.

In any event, Kill Bill, I think, may have been a seminal moment in our social adaptation to violent imagry. The violence is by turns beautiful, joyful, comical, symbolic, profound, and devastating. The House of Blue Leaves is naturally a standout moment, and it may have "jumped the shark" before this was even a thing - the sort of scene that could have recalibrated what we would consider “obscene” violence going forward.

Rewatching that scene this time, it was violent but not shockingly so, which makes me realize just how far the world has moved on in the 14 years since Kill Bill Vol 1 came out. We are, more than ever, saturated in intensely violent imagery, particularly those of us with a penchant for edgy cinema (or TV/video games/books), and I find myself wondering what role cinema has played in helping us to manage this inevtible amplification in exposure to violence, and in turn what debt we may owe Tarantino in particular.

Returning to Kill Bill was clearly a rich and rewarding experience for me. However, there was one particular reason that I fell truly madly deeply in love with the films this time: an essay I encountered just prior to watching (link shared below), which suggested an allegorical framework for the film that, quite frankly, made it more coherent, meaningful, and affecting. The premise is that there are many incongruencies in the films that resolve into lucidity if we consider Beatrix Kiddo’s quest to kill the Viper Gang in the light of the Buddhist path to liberation from the five traditional sources of suffering.

Kill Bill is an homage to much, but at it’s heart of hearts is kung fu and samurai cinema, and that cinema has always existed within a Buddhist ether. Furthermore, Uma Thurman -- Tarantino’s avowed co-creator of Kill Bill -- grew up in an intensely Buddhist household as the daughter of an Indo-Tibetan Buddhist professor, and one of the very first Westerners to become a Buddhist monk. Thurman herself is not especially religious, but considers herself more buddhist than anything else.

Either way, Buddhism was clearly a significant part of her cultural upbringing, as well as the culture of Tarantino’s cinematic upbringing. Tarantino was also so committed to authentically channeling the ethos of Eastern cinema that he insisted on shooting it in China with Chinese and Japanese creative teams and crews.

The allegorical potential becomes even more compelling when you consider that the path to liberation from suffering generally entails the eradication of five "poisons" -- pride, anger, doubt, ignorance, and attachment -- and how each of Beatrix Kiddo's five nemeses seems to evoke one of the five poisons, and are eradicated in their traditionally required order no less. I am no Buddhist, but I have an affinity for its philosophical sentiments, as I think many of us who enjoy a lot of Asian cinema do; if you’re interested in watching Kill Bill with fresh eyes (even if you’ve already made the buddhist connection yourself) then I encourage you to peruse this riveting essay in full.

Tarantino has said, quite vehemently, that Kill Bill is “just” a revenge film, and there is so much to unpack visually (and aurally) that its easy to simply marvel at its sublime interlacing of homage and originality. But there is an undeniable depth to the film, encapsulated in Uma Thurman’s at times blood-curdling performance (remember he wail of despair upon awakening with no baby?), that it demands we take it more seriously than simple entertaintment.

Quite what the depth means has always seemed elusive to me, particularly the gravitas given to the closing scenes with Bill, and why a film seemingly devoted to violent vengeance culminates with what amounts to loving euthenasia. But whether intentionally allegorical or not, awareness of the buddhist threads woven in have revealed to me hidden coherence and meaning and poetry that has elevated this film to the sublime.

Tarantino’s subsequent films have all been sublime in their own ways, but I don’t know that any have or will surpass the sheer cinematic joie de vivre on screen in Kill Bill. And in the end, that is probably why I love Tarantino -- because he exudes love for the art as a whole, as well as for the craft. Kill Bill feels like the confluence of two waves -- one the love of film, the other the love of film-making. At the point of their convergance is Kill Bill: peak Tarantino.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.

(1)-thumb-80x80-93563.jpg)