Full Disclosure: ScreenAnarchy's Lists of Shame - March (Part 1)

Seven Samurai (dir. Kurosawa Akira, 1954 Japan)

Winner of the Silver Lion, Venice Film Festival, nominated for 2 Academy Awards

The remarkable thing about Kurosawa's Seven Samurai is not that it breaks ground or does anything particularly new. No, by this point we've all seen this basic story structure - a downtrodden village enlists the help of rogue warriors to protect them from bandits - over and over again. It wasn't particularly new when Kurosawa did it and it's even less new now, with Kurosawa's film serving as the basis for American films as diverse as The Magnificent Seven and A Bug's Life. What makes it so remarkable is that decades later, with its influence looming large over countless other films, it still feels fresh and vital. It comes down to execution and attention to detail essentially, Kurosawa's staging and shot selection still impressive and his ability to balance such a large cast of diverse characters quite remarkable. Over familiarity kept it from being - for me, at least - blow-the-doors-off astounding, but it is still a very, very solid piece of work.

Seven Samurai is perhaps the first black and white film that left me picking my jaw off the floor. Nothing could tear me away from the screen. It is epic in every sense of the word and yet, somehow very intimate. I have seen other Kurosawa films, but nothing prepared me for the under-stated, effortless eloquence of this definitive tale. The hype and adoration is entirely justified and it is a film I feel I will be watching time and again. Every frame is utilised perfectly, not a single moment of its 3.5 hours is wasted among these incredible protagonists. I almost fainted when it came to that ending, and felt compelled to re-watch it immediately. I felt as though my senses were lying to me. Any contrarian view goes out the window, Seven Samurai is a god-damned masterpiece and one of the best things ever created on this Earth. Words can not do justice to the experience and I have defied logic by not watching this essential work until now.

Of all the films on my List of Shame, Seven Samurai is the only one that I feel truly ashamed for not having seen until this month. In fact, I'm pretty ashamed that I, a film scholar, have now seen only three Kurosawa films (the other two being Ran and Rashomon). Chalk that up to too many films in the world and only so many hours in the day. Needless to say, I came to my viewing of Seven Samurai with a great deal of knowledge about it, its place in film history, its importance and influence. This did not mean I was disappointed, far from it. I can see its influence on action and adventure films, crime films, buddy cop movies, etc.

Rashomon is a favourite film of mine, and so I was thrilled to see Mifune Toshiro here as well. He truly was a force of nature as an actor; one cannot help but be mesmerized by his mad energy and subtle brilliance. I have seen the Hollywood remake, The Magnificent Seven, and so watching the differences in Seven Samurai was interesting. Gone is the grandstanding and clearly delineated line between good and evil, replaced by a great blurring between the villagers, the samurai and the bandits. I love how Kurosawa made his sets, his actors, even the lighting, so dirty, so grimy, really emphasizing the poverty of the village, the desperate circumstances. The conveyance of the complexities of Japanese culture was shown in the smallest and largest gestures, each one connecting to the other like a web. I was also impressed with how well the violence was handled. I don't know enough about Kurosawa to know if this was just his style, or if there were restrictions on representations of violence in Japanese film at that time. But as someone who has grown very weary of excessive violence, what and how it was shown was a breath of fresh air.

It also made me lament the possible slow demise of the movie house. I had to watch the film on a computer, which definitely marred my enjoyment. This is a film that demands the big screen. I know that retrospectives of filmmakers like Kurosawa are common enough, but what about the future? So many films have no reason to be shown/watched on a big screen. Is the audience for films like Seven Samurai large enough to keep big screens going? Or will that only be the reserve of films with big special effects but nothing to say? Next time it comes to town, I will definitely be booking a ticket to see this marvel of a film on the big screen.

Eraserhead (dir. David Lynch, 1977 USA)

David Lynch frightens me. Not the man, of course, but his work: Blue Velvet, Wild At Heart, Twin Peaks, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, Lost Highway and Mulholland Dr. have all unnerved and unsettled me at a sub-atomic level. Not every moment in every one, but enough so that I approach re-viewing opportunities with extreme caution. It wasn't always this way, because I began with The Elephant Man and Dune, visually enchanting, markedly "different" films that I loved.

Maybe things would have been different if I'd started with Eraserhead, but the only friends who raved about it at the time were potheads, whose opinions were notoriously unreliable. So I declined invitations to attend one of the numerous midnight screenings that always seemed available in late 70s/early 80s Los Angeles. Now, having finally struck it off my list of shame, I think my much younger self might have hated it: the non-narrative approach, the sexual panic, the disgusting bodily fluids. But my 2013 self dug it all. Bracingly weird and disturbing and confounding and hilarious, Eraserhead is a brilliant forerunner, mapping out the terrain that Lynch would later explore in greater depth and with more brazen visual schemes. Here is where it truly began, though, an epic, feverish nightmare that never ends.

Solaris (dir. Andrei Tarkovsky, 1972 Soviet Union)

Winner of the Grand Prix and FIPRESCI Prize at Cannes Film Festival

Blame it on a clash of cultures, but some films just don't age all that well. Some 40 years on, it would unfortunately seem that Andrei Tarkovsky's Solaris is a bit too tinged with vinegar, at least for my taste. The big problem is that it all feels a bit obvious. From the beginning of the overlong first act where we watch a painful home video (good cinematography in those home videos) of one pilot's testimony of his psychedelic trip to Solaris, it is pretty clear that the visions these people are having are psychological. Yet the team sits around and debates it like perhaps there really is a 30-foot baby on the surface of the planet.

These head trips continue once Kris Kelvin (Donatas Banionis, who is pretty great) makes it to the space station, but it's as clear as its over-lit set where things are headed. Also, isn't Kelvin a little unstable to be sending on such a critical mission? Pair this with odd soviet era flips of film stock and really poor visual effects and it just seems that Tarkovsky was making every decision poorly. I'm sure there is some rich material in the psychological study, but I was too disengaged to get past the charred skin and into the tender meat of the story. I am interested, however, to now go see how Soderbergh handled the subject matter.

As a sci-fi geek, I was recited to finally watch the original Solaris, despite what I'd heard of it being really slow, strange and esoteric. Turns out, it's really slow, strange and esoteric. While there is some stand-out production design, ultimately the film feels dated and obvious, despite it's enigmatic and subtle approach and its attempts at answering timeless questions. While it might have been ahead of its time when it was first made, today it feels behind the times, leaving it greatly inaccessible to a contemporary audience, broadly speaking. Perhaps it's just too heady or simply too Russian for me, or maybe I just didn't get it, but for my money, there is a lot more I would've rather done with those three hours.

My first run-in with Tarkovsky's Solaris was as a teenager in the early 1980s, when the Dutch state television broadcast a series of classic science fiction films. I just had discovered Space 1999 and Star Wars, had decided I loved science fiction and was frantic to see anything with a space ship in it. But Solaris was nearly three hours long, and on late at night, so my parents were stern and said no. Most of my classmates who DID get to see it didn't finish it. They also told me that it was NOTHING like Star Wars.

Today I am still a big fan of science fiction even though I understand slightly better what the genre is supposed to be about, especially when it's not being confused with escapist fantasy. I actually did see (and love) the Steven Soderbergh adaptation of Solaris, but Tarkovsky's version didn't attract me. Length, reputation, childhood trauma... I don't know the reason but it never filtered to the top of my to-do list. Until now...

And guess what? While Tarkovsky's Solaris definitely isn't the escapist fantasy I mistook for science fiction, it isn't science fiction either. Despite its setting and a lengthy tell-not-show at the start which reeks of science fiction, this is psychological drama first and foremost. Tarkovsky is not at all interested in the exploration of new things, or their impact on society. His big question is why everyone has traveled so far from their nature, from their roots. The plot of Lem's book is only slightly used, and then only to show the main characters that they need to reflect on the empty fakeness of space, as opposed to getting things in order on their real Earth. Unlike what happens in Soderbergh's version, Tarkovsky allows no wonder at the unknown, and no emotional solace to be found there for his protagonists.

If it sounds like I'm slagging the Tarkovsky version I apologize, although I do fiercely disagree with his view. His Solaris is a masterpiece of mood and reflection, definitely worth viewing. The compelling and (frankly) terrifying end will stay with me a long time. But DAMN am I glad I didn't watch this back when it was on the telly. I sure would not have appreciated it, and it might have put me off of true science fiction for even more years than my infatuation with escapist fantasy ever did.

Here's a case where the commendable goal of being intellectually rigorous turned into a pathetic episode of procrastination and self-denial: I'd long-wanted to see Solaris, but was adamant about first reading the Stanislaw Lem novel (which I own, so no excuses there), and then swiftly following up the viewing with Steven Soderbergh's 2002 remake. The result of all this planning, though, was that nothing at all happened - until this series forced the issue.

The reason I'd so wanted to see Solaris is that I quite like Tarkovsky. Granted, while I admired Stalker (1979) when I saw it years ago, it was a bit over my head; I do adore Andrei Rublev (1966) unconditionally, though. The self-denial part enters the picture because now I can't believe Solaris was so casually on my "some day" list - that's how much I've been blown away after finally catching it.

In terms of the ol' "art film vs. genre film" dichotomy, I was prepared to respond to it primarily as the former, with genre simply being a vessel for the artiness. (One of my biases: if a director doesn't regularly work in a given genre, his/her foray into it is likely opportunistic, or for ulterior motives). Yet the sci-fi elements in Solaris are terrific. Immediately one senses the film's influence on an entire subgenre of madness-in-space flicks that combine surrealism, subjectivity, and existential themes to explore the value of humanity, human-ness, and, directly or indirectly, Earth itself. Moon (2009), Pandorum (2009), Event Horizon (1997), and Sunshine (2007) all fall into this category.

Obviously Solaris is much more meditative in this respect - others might less charitably call it "boring" - but I found its slo-mo pacing, repetition, long silences and abstracted visuals to be perfect for inducing dreamy reverie, which I assume is one of its goals. In this sense, Solaris is not so much a forebear of the above-cited genre films but, in its focus on contemplation and loneliness, more an extension of religious and/or prison films. In fact, Solaris has much more in common with something like Life of Pi (2012) than your typical sci-fi film. Both are about extreme isolation and the huge importance, and arguably bigger risk, of connecting... even if that is with a man-eating tiger or an inexplicable "ghost. "

It's that obsession-with-the-unreal theme that hit me hardest. Now, I'm not trying to be fancy and "meta" for the sake of it, and have absolutely no evidence that this was on Tarkovsky's mind (it certainly wasn't on Lem's), but I couldn't help experiencing Solaris as a commentary on film culture itself. How many of us are happy to spend our days in communion with a mere reflection of real life, convincing ourselves that any difference between it and actual engagement with the world of other humans is a matter of minor significance?

Quadrophenia (dir. Franc Roddam, 1979 UK)

Of all the titles on my list of shame, it is not the classics of Hong Kong Cinema that embarrass me most, but Franc Roddam's 1979 adaptation of The Who's rock opera. You see, I'm a Brighton lad, and as a teenager growing up with the sea air in my lungs and the caw of the seagulls in my hair, Quadrophenia stood alongside the likes of Top Gun, Withnail & I and Ferris Bueller's Day Off as required viewing amongst my friends. Not that I refused to watch the film until now as some kind of defiant scream for independence, it just somehow always passed me by. For me, Phil Daniels was just that guy who chimed in on Blur's "Parklife", and The Who were just another British rock band that wasn't Led Zeppelin or Pink Floyd.

Now that I have seen it, I must confess to being pretty angry with my younger self for not making the effort sooner. I am confident that Quadrophenia would have spoken to me on a number of levels: the story of Jimmy, a pill-popping young Mod who is struggling to make sense of work, money, birds and life in general as he does his best to stay off his his head and out of the Rockers' way until its time for the weekend and a chance to go dancing and brawling. In many ways the British answer to Dennis Hopper's Easy Rider, Quadrophenia stands up incredibly well, featuring an insanely good soundtrack from The Who, a parade of future stars of British TV and Cinema all at a scarily young age, but most of all a raw energy and youthful arrogance that advocates the importance of a sharp tailored suit, killer scooter, and going out in a blaze of glory.

Monty Python's Life of Brian (dir. Terry Jones, 1979 UK)

Whenever I introduce myself to a British comedy nerd, they inevitably make some joke I don't get, like, "Are you the Messiah or a very naughty boy?" I usually look at them inquisitively, maybe shake my head, and then wait for them to explain to me that it's a reference to Monty Python's Life of Brian, and also that my name is Brian. At some point, for reasons beyond my understanding, I developed a bizarre affection for these awkward exchanges, and began to actively avoid seeing the comedy classic.

But alas, now I get all the jokes. I watched Life of Brian at 11:00 am on a Friday morning alone in my apartment. This is not normally an environment that's terribly conducive to laughing and getting the most out of comedy. However, I kept a tally, and the mis-adventures of the boy born next door to Jesus Christ made me laugh out loud fourteen times, and provoked another dozen or so chuckles besides. Not bad! I was also impressed with the satire, which still felt biting today. I suppose the idea of people searching blindly for a saviour to give their life meaning is pretty timeless.

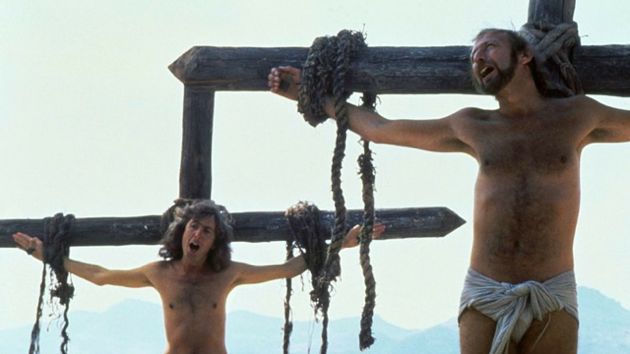

Like most Monty Python movies, the jokes were a bit hit or miss for me, and often I admired the troop's efforts more than I actually responded to them. But then came the ending, which for some reason, no one had told me about. (Spoilers abound, if you're one of the handful of people who has never seen this one) I'm talking of course, about the crucifixion musical number. Not only was it unexpected and hilarious, but also surreal, artful, visually inspired, and actually kinda moving. And the song "Always Look on The Bright Side of Life" is catchy to boot. Suddenly my messy, empty apartment didn't seem so depressing anymore.

Babe (dir. Chris Noonan, 1995 Australia)

Winner of the Academy Award for Best Visual Effects, nominated for six others including Best Picture and Best Director)

I have mixed feelings about the experience of watching Babe, although ultimately it was a joy. Compared with my first two choices watched in January and February - Lawrence of Arabia and Gone With the Wind - Babe is a mere cream puff of Cinema. After Gone With the Wind had invigorated me into seeking out other monumental classics that had almost made my list, I was now faced with an Australian family film. I'd previously avoided Babe as I tend not to like talking or singing animals in movies, and this seemed to promise both.

However, after years of working in the Australian film industry, Babe was a film I was truly ashamed not to have seen - to the point of faking having seen it in many conversations. So I started watching it, to discover instantly that this film which for years I'd known as an Australian film was actually an American film, at least in terms of the accents. This was a shock, and I promptly switched the film off after trying to get into the first 20 minutes. I'd been prepared for a quaint Australian film, not the glossy American movie this seemed to be.

A week or so later I thought I'd give it another go, and adequately prepared for what I was getting into, I settled into it and found myself completely charmed by the little pig and his underdog story. Three elements in particular really sealed this for me. First, James Cromwell's performance. I'm not surprised he was nominated for an Academy Award for this. It's so understated and with such little dialogue, but surprisingly powerful by the end.

Second, there's the creature work. Such a seamless integration of real animals, puppetry, VFX and who knows what else (frankly I don't want to research it and spoil the magic) that even now, 17 years later, it still holds up remarkably well. And third, there's the look and tone. Fittingly this is almost cartoon-like in parts, with seemingly exaggerated sets and 'big' characters - like the very best Roald Dahl adaptations - which only helps sell the overall children's storybook vibe it reaches for. I could have done without the annoying singing mice though.

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.