SCREENANARCHY Presents 100 Years of Nikkatsu at TIFF Bell Lightbox

My knowledge of Japanese classic cinema is pretty much formed by the big three: Kurosawa, Mizoguchi and Ozu. The films showcased as part of this series were a generation fighting against some of the more formal methods of these three masters, while drinking in the slick style of nouvelle vague kineticism from France, the stark nihilism of 30s and 40s Gangster films, and even the broad and epic twang of the spaghetti Western. Yet this is classic auteur stuff: Cheap, quickly made genre films that nonetheless have the voices of their directors coming through loud and clear, illustrating how artists can take even lowly procedural films and craft something truly special.

As I talked about briefly in my article about Star Wars and Kurosawa, the feedback loop between Japanese and Western cinema is a pretty fascinating one, with clear examples show from the three films of the series TIFF sent me to review.

Rusty Knife uses the metaphor of the retired weapon throughout, crafting a punchy, Godard/Truffaut-inspired gangster tale of a former killer trying to make a go of the clean life. When he's finally forced to act once again, the tale plays out in a way that's obviously familiar, but done so with an elegance and class that's quite refreshing even decades on.

Rusty Knife uses the metaphor of the retired weapon throughout, crafting a punchy, Godard/Truffaut-inspired gangster tale of a former killer trying to make a go of the clean life. When he's finally forced to act once again, the tale plays out in a way that's obviously familiar, but done so with an elegance and class that's quite refreshing even decades on.Amusingly, the director Masuda Toshiro would go on to make far more explicit allusions to the likes of A Bout De Soufle with Velvet Hustler, but with this film you can really see his fascination for that burgeoning style of filmmaking. Unbeknownst to me, I actually own one of his works, as he (along with Richard Fleischer and Fukasaku Kinji) would go on to direct the American/Japanese co-production Tora! Tora! Tora!

While the film borrows heavily from these various elements, it does manage to have its own charms, although it's pacing is a bit staid for modern audiences. An even more zippy (and frankly bizarre) film is the Nikkatsu production of Suzuki Seijun's 1958 film Tokyo Drifter. I'd long seen the image of the bright artwork showing up as one of a myriad of discs in the Criterion collection that I thought I'd get around to one day, but I was completely unprepared for this mad dream of a genre pic.

While the film borrows heavily from these various elements, it does manage to have its own charms, although it's pacing is a bit staid for modern audiences. An even more zippy (and frankly bizarre) film is the Nikkatsu production of Suzuki Seijun's 1958 film Tokyo Drifter. I'd long seen the image of the bright artwork showing up as one of a myriad of discs in the Criterion collection that I thought I'd get around to one day, but I was completely unprepared for this mad dream of a genre pic. Shot in claustrophobic sets that are often preposterously theatrical, this is a bold, brash film, straight out of the pop-art of the mid 60s, creating a delicious double bill with the likes of fellow 1966 film, Antonioni's Blow-Up. Conceptually the film actually ties in nicely to Rusty Knife again showcasing how a retired Yakuza must come to terms with his abandonment of violence as a tool. It's not so hard to see the long shadow of a demilitarized Japan looming over both films, as each film showcases characters trying to remain virile while having their long-formed skills of action and retribution silenced for a greater good.

Naturally, things can't remain quiet for long, but when we're greeted to Go-Go dancing teens hopping atop acrylic floors, draped, cathedral like white hallways or bright yellow cabaret theatres, you know you're in for something beyond the normal gangster pic. Borrowing as much from MGM technicolor as from the Warner Gangster film era, this is a impeccable collision of genres, with some stellar performances from the fine cast.

The film also echoes in more subtle ways the devices of the Spaghetti Western, especially in the form of a much repeated title track that plays over and over, the Yakuza wandering from town to town as a singing linesmen would ride the rails, or a cowboy whistling as he shambled from coral to coral. More explicit Anti-US sentiments are found in a completely bizarre bar brawl, a scene that presages a very similar over-the-top punch up in Brooks' Blazing Saddles.

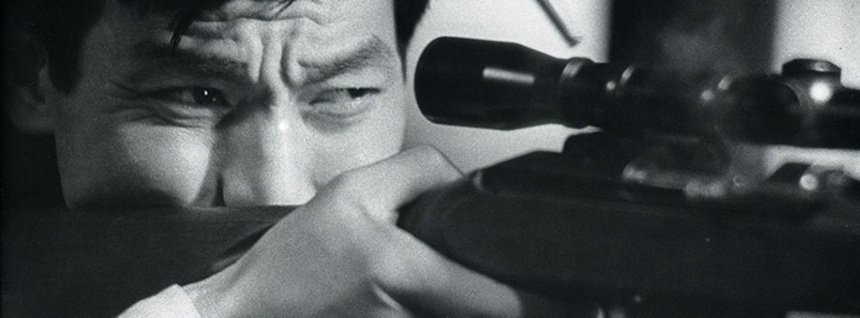

Finally, there's the gem of the bunch, A Colt is My Passport directed by Nomura Takashi. It stars a preposterously chipmunk faced Joe Shishido (I found out after the film this was the result of plastic surgery!) as a capable Yakuza hitman that delivers on his hired task, only to find himself hunted by the very people who hired him. This is the most explicit of the ties to the Eastwood-style character, an almost perfect transplant of the taciturn anti-hero motif into a Japanese setting. There's even a whistling soundtrack to make the connection even more formal.

Finally, there's the gem of the bunch, A Colt is My Passport directed by Nomura Takashi. It stars a preposterously chipmunk faced Joe Shishido (I found out after the film this was the result of plastic surgery!) as a capable Yakuza hitman that delivers on his hired task, only to find himself hunted by the very people who hired him. This is the most explicit of the ties to the Eastwood-style character, an almost perfect transplant of the taciturn anti-hero motif into a Japanese setting. There's even a whistling soundtrack to make the connection even more formal.Shot in a strong visual style, it's hard to watch the film now and not be amazed they haven't ruined it with numerous remakes. Sure, echoes of subsequent films abound, but I haven't yet seen a film that does it quite the same way as Colt, a testament to its brashness and timelessness.

These are three are part of a dozen films that Brown has programmed, including the likes of Suzuki's latter film Branded to Kill and Hasebe Yasuharu's astonishingly titles Stray Cat Rock: Sex Hunter. Prior to this assignment this entire series of films was a mystery to me, and if they're any indication of the quality of the lot, then Toronto audiences are in for quite a treat indeed.

Tokyo Drifters: 100 Years of Nikkatsu runs at the TIFF Bell Lightbox in Toronto from January 19 to April 6, 2013

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.