Movies as a Cassandra Complex: A Conversation with Walter Chaw on Global and Personal Apocalypses of the 1980s with MIRACLE MILE

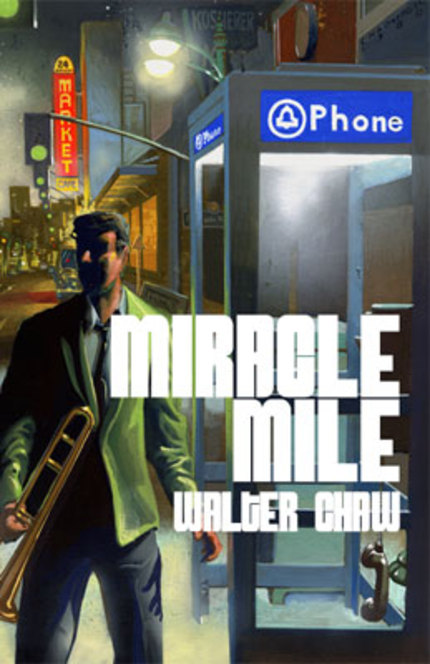

The thought of reading a 200 page essay-review hybrid, a monograph, on a single film may appear to be a daunting task. Some time ago, Johnathan Lethem and Softskull Press proved just how delightful and rewarding that can be with their series of monographs starting with John Carpenter's They Live (but also, Death Wish, Heathers, and others). These books are not stories of production, or interviews with the director, but rather a single vision of what a particular film fits into the mental space of a single author. Walter Chaw, the principle (and often cantankerous) critic over at Film Freak Central for over a decade, takes the concept to the next level with his Lulu published monograph on Miracle Mile. Steve De Jarnatt's film wherein Anthony Edwards picks up a pay phone receiver at 4am outside of a Los Angeles coffee shop and discovers the US military may have launched a full out nuclear assault on Russia, with potential retaliation hours away. The film is a slightly forgotten bit of 80s paranoia that has fallen through the pop cultural cracks in the past 25 years, but proves quite ripe for either a re-harvest or an autopsy. Writing very much in the context of his personal life, a suicide attempt, and a rooted cache of father-son baggage, Chaw goes back and forth between the films vast collection of signs and wonders and how the effect they can have on both the characters in the film, and those watching the film. A quote not in the conversation below, but telling: "It is really easy to critique or defend say, the recent Nicholas Winding Refn films. Valhalla Rising or Drive. It seems like you are wearing a monocle and eating cheese when you do so. But to defend THIS..." And he does, with a sense of passion and intimacy.

In a long-form, nearly shot-by-shot analysis of the frame, there is plenty of opportunity to tangent off into subjects as diverse as the sleepy denial of Reagan's Morning in America, or how any apocalypse is romantic by nature. Miracle Mile is a movie with an astonishing cast of C-grade character actors, and reading Chaw make connections and observations on how, where and possibly why each of these actors were used, is as revelatory as is his personal reasons for latching onto this film in the first place.

As a rather large enthusiast of both Chaw's writing at FFC and with Miracle Mile being one of personal sweet-spot genre films of the era (along with The Hidden, Near Dark, The Stuff, David Lynch's Dune and most of John Carpenter and Paul Verhoeven's 80s work) it felt like the book was like a personal gift from the author. That there was so much raw red meat in the text, or rather, that I learned a hell of a lot of things that I thought I know about what was up on screen in the film, left plenty for me to chew on. Not just curious trivia bits, such as that the Anthony Edwards role was supposed to go to Gene Hackman at one point, or that the short-order cook who freaks out at Johnie's Coffee shop also played the brisk desk sergeant in Robocop, but rather just how much relationship folly (and hubris) can be crammed inside a paranoid thriller, or the underlying self-awareness in using the word "Jigaboo" in His Girl Friday or the Marshall McLuhan significants of USA TODAY vs any other newspaper.

Suffice it to say that if you are a fan of the film, then this Monograph is a must-read. If you've yet to encounter the film then there is no better guide through-out a discovery than Chaw. (Note: The 35mm print of Miracle Mile is, sadly, rarely screened, but it is easily found on VHS or DVD, albeit in cropped form.)

As a follow-on to my enthusiasm for the book and the film, I tracked Walter down and got him to brave the technical persnicketies of Skype from his Colorado home. The conversation that followed has an equally tangential but also vital and earnest vibe as it flows from John Hinkley Jr. to the Aurora Shootings practically in Chaw's Arvada back-yard; the role of a critic; the ebb and flow of popular culture; the operatic nature of Cronenberg's The Fly; the subversive details in Back To The Future and the horror and possible necessity of romantic deceit. Below is a slightly abridged version of that conversation:

Kurt Halfyard: First off, with Miracle Mile, it is excellent to read you writing about something you love. I think there is some small amount of infamy associated when you are writing both critically and negatively. It also nice to read you writing in long form. How was the experience of writing a 200 page monograph on a single film rather than 600-800 words on film from week to week?

Walter Chaw: It was really liberating. I felt, after doing this, for, how long has it been, about 12 years or so, I was losing something. I was not looking forward to seeing a lot of movies anymore. I beginning to feel like a bitter old man looking around in a movie theatre, thinking I don't want to be around these people right now. I don't want to be here for a Miley Cyrus movie. It is one of the hazards of making one of your passions into your job. Suddenly you feel, about ten minutes into the remake of Total Recall that you know you are not going to like it and yet you are stuck. You are not only stuck but you have to go home and you have to write as you said, 600 to 800 words on it. So you are spending all your time with material you do not like. You can begin to resent all movies in a way, when it only happens three or four times a year that you are really pulled out of that funk with a Tree of Life. But, to be able to sit down and sort of exorcise some personal demons while I'm working through something lengthier, I can try to figure out what makes me the sort of asshole that I have become. Why do I like the things that I like. For the longest time I thought that there was some kind of absolute standard for good and an absolute standard for bad. And I still believe that is true, but I believe that I have become a lot more liberal and understanding on peoples point of view. I was a lot meaner earlier on about peoples opinions on things. But now I feel as long as you recognize it is not foie gras, I'm OK with you liking Taco Bell. That's fine with me. So. I've gone far afield here. It was really nice to write about something in a way that I wanted to write about something. The format of how we doing things at Film Freak Central, my editor Bill, is so open already, but just to be to go on a 10 page digression about 80s era Twilight Zone and the Reagan Era and things that I know about with out knowing about it. The things I grew up with. It was really fun. I am not sure I have it in my to do it again, but for about 200 pages or so, it was really nice to let go.

KH: You certainly realize, after watching the film, or in reading your book, just how Miracle Miles is one of the most 'Eighties' films ever made. It is so Eighties that you feel it is almost artificial in how it looks. When Anthony Edwards is wandering though the 24 hour Gym, my lord. But then as it was actually made in the 1980s, you have to smile at it's strange off putting veractiy. One of the delights of the book is the tangents. Where do you draw the line between letting the book breathe, vs. staying on target and going almost shot by shot though the movie?

WC: I didn't have a set length. If I was left to my own devices, that would be the length that I write almost everything. I'm really wordy, if I didn't have a good editor, to give me a sense of what I need to be talking about, that is what I would talk about. I am more often restraining myself from returning in 10 page reviews on Para Norman. I really want to talk about everything else. What a film makes me remember, that I was really interested in Monster Squad way back when. It really takes me somewhere else. I think the format that I have been writing in for so long, I just don't talk about a lot of the stuff that I do want to talk about. Partly it is the format, partly it is the hate-mail. I used to answer all that mail. I used to be so flattered that anyone would write something back, whether it was positive or negative. You've probably had that experience as well. You feel that you should answer this because they obviously want to engage in conversation. Often, however, you find through difficult experience that few want to have a conversation. Usually, they just want to yell at you. That has changed a lot about how I write, I do not make as many references to myself as I used to. I don't try to dig too deeply in how a film made me feel at a personal level unless it is a movie like Tree of Life. Even Superman Returns, I spent a lot of time with that one. Or Jackie Brown and the Tarantino films that really move me. Anyway, I have began to self-edit a lot. And this book allowed me to not self-edit.

KH: Here is a web question. I know that Film Freak keeps their format consistent, but it is not like a newspaper where there is a finite amount of column inches. Isn't the web a place where you can be a bit more self-indulgent in terms of review or feature lengths? Scrolling down isn't hurting anyone. Why make that call to 800 words instead of 2000?

WC: To Bill's credit, he has never given me any guidelines. That is why we still have a relationship. Even when studios were shutting us out, or we were getting in trouble. I think those guidelines are self-imposed so I do not ramble. So I do not spend so much time with a movie that does not deserve it. To spend so much of myself on something that is not making a connection with anybody. When I'm not actually talking about the movie anymore, when I'm just talking about something that I'm personally curious about. So yea, it's self-editing more than anything else.

KH: One of the things that is quite striking to me, is just how much you blend criticism and analysis of Miracle Mile with the personal. Since it is an apocalypse film, you have a lot of personal apocalypses are woven into the text. I think more than your reviews, I felt voyeuristic at times reading the book, you really do throw yourself out there in an intense way.

WC: Yea, how does that work out?

KH: It works out fantastic. When you make it really personal, criticism becomes far more interesting to me. What is a movie other than a mirror. When you look at it. You mentioned Tree of Life twice. I think that people who really went over the moon about Tree of Live, see something very vivid from their own life or childhood. I think it is the Brad Pitt and family stuff that makes people go nuts over that film over the macroscopic Universe stuff, because it is those intimate details that lock you in. In the case of your book, your suicide attempt, your father, and even encounters with a girlfriend. This is pretty raw stuff.

WC: I always feel the best criticism is autobiographical in a very intimate way. Even though I don't like Pauline Kael all that much, there is a question that someone asked her at the end of her life why she never wrote an autobiography, or a memoirs, and she pointed to her whole body of work and said, I have, there is all of that. I think that if you do a good job, you reveal more about yourself than about the film. The reasons you like Inglorious Bastards are probably different than me. The intensity may be the same, but the particulars are probably different. That is sort of what I wanted to do with writing in the first place. The reasons I began to do film criticism was my Father's first heart attack, the one that didn't kill him, and I thought, I need to get back to what I wanted to do. It was poetry criticism. But nobody wants to read another book on Keats, and I don't want to write it, but here is film. Here is the possibility of producing criticism that doesn't necessarily give people something they need, but you are in a way giving yourself something that you need. If there is a film that really attaches to you, it is up to you to say, "Why this film?" Talking to you, or hearing people that have read the book, I'm still sort of shocked that anybody reads the things that I write. They are all kind of personal. If I'm bitchy about a movie. I get offended when a movie is not good. When a movie has no purpose behind it. It just exists and is not telling me something. A lot of the disappointment that I was having with film fed this project. For me to say, wait a minute, why movies anyway. What was it that made me turn to this stuff when I need it. And turn to this stuff over and over again. In particular, Why this movie? When I show it to other people, if they stick with it past the first twenty minutes or so, they are great. Like you say, it is so Eighties. A lot of people I know now are younger, maybe much younger, and they didn't connect with it in the same way; that they might think it is ridiculous. So there is something to autobiography to everything. Whether or not this book was good, I wanted it to be a document of who I was. So that my kids (or grandkids) could look back and say, hey, Grand-dad was an asshole but hey, he was genuine.

KH: A lot of your reviews occasionally send me off to Wikipedia, to maybe see where you are going with this or that.

WC: You see, it is pretentious! *Laughs*

KH: I think the obligation for people to understand everything that someone is writing, in same way that a stand-up comedian is referencing a wide variety of things in crafting his jokes, and not everyone is going to immediately get everything. Of course you want the audience to be keeping up, but for your own sanity, you cannot dumb things down to the point of reaching everyone all the time. You might lose a few people, but you've got to throw it out there anyway. Or at least in your own mind you feel that that makes a point really well, even if only 30% of the audience may know what I am talking about.

WC: Well the joy of Wikipedia, or the joy of Google is that everyone can become an knowledgeable in a couple minutes. I always felt it would be far more pretentious of me to assume that you didn't know anything, to presume that you do not know words, or have not having read what I have read. I never presume that. For me my audience is actually me. For the ten million things that I do not know. This is something that I do know. I would never presume to talk to you like an idiot. I find that to be far more pretentious. If we just sit down in a room and talk like equals, that is far better.

KH: Miracle Mile is one of the quintessential eighties movies. But it is also a paranoid thriller. And when I think of paranoid thrillers, I generally think of the 70s. The Conversation, Three Days of the Condor, and those Charleton Heston science fiction movies. But then, if I think a little more, the 80s did kind of have it going on in the paranoid thriller department. The Dead Zone, the three Cronenberg flicks, The Thing, Brazil, Vampire's Kiss, Invaders from Mars, Southern Comfort, Blow Out. I want to say The Warriors, even though it was 1979, I feel it was a movie that kind of ushered in the 1980s. Where do you stand on the cinema of the 1980s in general.

WC: I do feel that film is a really remarkable social mirror, the frogs in the swamp, the indicator species; the first thing that falls when there is some sort of toxin. So you get in 1968 and Night of the Living dead, the best civil rights movie ever made, and then you get the 1970s paranoia. I still think that is the best decade in film anywhere, ever, from Bonnie and Clyde to Raging Bull. An amazing period. And 1980s is very much indicated by the Regan era, and an attempt to drag us kicking and screaming back into the Eisenhower years. In which we plastered over all the discomfort we have in the US. By re-fighting Vietnam over the decade, and so it produces other quintessential 1980s films like Back to The Future. You go back to the Eisenhower era to find out there is violence and racism and that your mom is a slut. That is essentially Back to the Future. There is an interesting counterculture that happens. That makes the 80s kind of like the new 50s. What you are actually doing, is unearthing all the same anxieties and fears that the 1950s had all this nuclear paranoia and red scare.

KH: The Eighties and Fifties were the two Cold War peaks.

WC: Exactly. And did have the same consequences as the 1950s. Suddenly we are very suspicious of our neighbors. And the Evil Empire and all of that. Eighties film reacted to it in the same way as Fifties film. You have The Wild One, East of Eden. Movies that are bubbling up from underneath, so that we can prepare ourselves for nude sex scenes. I sort of wonder at the end of the eighties if we were going to start seeing movies like The Wild Bunch and Rosemary's Baby in the 1990s. And sure enough in the late 1990s, Fight Club and The Matrix bubble up. They say, wait a minute we have been in this digital/analogue struggle, and digital has won. Then you move into the new Millenium and all the post 9/11 stuff. Film has always been this amazing barometer of where and who we are. It is not a trick to look backwards one decade and figure out what was going on. The trick is to figure out what is going on right now.

KH: It is funny that you mention 1999. I've always felt that that decade was an accidental attempt to squeeze the entire 1970s into a single year of cinema. The year is bloody insane.

WC: Amazing. Being John Malkovich, Iron Giant. Even stuff like Election. Uncomfortable stuff. You remember 1999 we were talking about nuclear missiles going off due to the Y2K bug and airplanes falling out of the sky.

KH: Buildings falling before they actually did, in the final shot of Fight Club.

WC: There is real prescience of 1999 and a real prescient about the best parts of our films. When we look at movies like Kick Ass, or the Christopher Nolan Batman trilogy, there is something extraordinary an unfortunately prescient. I really hope that the Batman films are wrong about the cynicism and nihilism, but they really feel correct. Of course what happened in my back-yard [Ed. Chaw lives near Aurora Colorado] with the shootings two days later. That is a long boring other conversation for a classroom, but I don't believe that film makes us, it reflects us in an essential and quick way.

KH: You brought up the final Batman movie. Miracle Mile ends with EMP, which drives the helicopter containing the two main characters down into the tar pits. It is almost the final word of an apocalypse in a single thing. All modern society ends because all electricity, technology, et cetera shut down. But in the Dark Knight Rises, and here is where Nolan has rather large clankers, to assume that the EMP is actually fully and easily self contained for enough money. It is one of the films best sight gags when Bruce Wayne walks up to the photographers that are annoying him at the benefit, and just uses his micro-EMP. He also has EMP contained and concentrated in a gun that he uses early on in the film. I'm not even sure what that is saying about our confidence in what technology can contain and harness. There is hubris, and then there is THAT. You say there is a lot of cynicism in the Batman movies, but the Dark Knight Rises might be the most hubristic act of self confidence on how we as a society feel about technology. I think those films work better in trafficking in images rather than storytelling and the EMP thing strikes me as an interesting dovetail with Eighties movies like The Day After and Miracle Mile. It was the end of society there, now it is just a key fob.

WC: I am so informed by that Eighties feeling about that. I found the end of The Dark Knight rises to be patently difficult. How does he keep flying the batwing when the blast goes off. Isn't he in the range of the EMP. I don't know what that says about us, either. But I agree with you about Nolan's clankers. I don't think narratively the film works at all. There are raging continuity errors, I wish I could be more specific, but something along the lines of Batman says something to Catwoman that has already happened, but he is talking about how they are about to do it. It has been edited in a way that clearly is more for mood and visuals than it is for sense. It is a fever dream unfolding and it is a fever dream of the 1980s. I wonder if the Dark Knight films are not a fever dream of the post 911 period. I was hoping in a way that The Dark Knight could exorcise some of those demons, but mainly we just want to seem go get our geek on with it.

KH: The one thing that the Nolan Batman films never addressed was the day-to-day social life in Gotham. They don't have time to do that in those movies, when they put in a school bus of orphaned kids in The Dark Knight Rises that is more for peril than any sense of what life is like in Gotham. You have to take it for granted. It always tells, but never really shows.

WC: Yea. I'm not sure that I would excuse it as time. I think if Nolan made a 6 hour movie, people would be thrilled. I also wonder if the Dark Knight and those Batman movies are more about Opera. That element of grandeur.

KH: Certainly the bombastic scores in those films would suggest so.

WC: Absolutely. You talk about Cronenberg in the 1980s. I always thought of his The Fly as an opera in the best sense of the word. It is this grand romantic piece. The way that the music rises to a crescendo and the hero commits suicide. There is this noble feeling to it. And the speeches are very much grand and over-written, very much like the Dark Knight. This is huge. This is Pagliacci. There is no real grounding or moderation. I think the best way to read them are as mood pieces - dramatic operas with gothic trappings that speaks to our time in a way that is uncomfortable. For me The Dark Knight Rises is a really great film that is a disaster as a narrative.

KH: I'm with you on that. Wasn't there actually supposed to be an opera made from The Fly?

WC: It did play for a bit. They got Eiko Ishioka, the lady who did the costumes for Immortals and Coppola's Dracula from the little tidbits I've seen on YouTube it looks insane. It looks perfect. Either way, I can see The Dark Knight as going that way too.

KH: Hopefully it would do better than Spiderman Musicals!

WC: *Laughs* When you think about the eighties. My son just started getting into Raiders of the Lost Arc, and that is essentially a WMD movie, and the good guy wins by pretending it is not there. You are closing your eyes and turning away. How many movies of the 1980s were that way. Think of Ghostbusters, where essentially they are wearing nuclear generators strapped to back. There is something quintessentially eighties about that. And if you loop back to Dark Knight. I think people get caught up in story lines. You get caught up in cultural story lines. And if the cultural story lines in the 1980s was apocalyptic, then you are going to try to kill yourself and think it is romantic. There is a part of the book that I wrote about Heathers, because that one is a biggie for me as well, there is this part about Heather Chandler where she says, "Did you have a brain tumor for breakfast?" Died of a brain tumor ten years later. The strangeness of that circularity. There is a story line that movies identify to us about our culture. And if the story line is about some people who want to burn things down, or that some people want to watch the world burn. Even Memento, the movie that he made before 9/11 had this. If that is the story line he is presenting then the shooting makes an absolute sense. Here is a guy, the shooter, who is standing in front of the movie and what everyone in the theatre said is that they thought that was a part of the show. He wanted to be a part of the show. The is the story line here.

KH: We process in narrative.

WC: We are fulfilling cultural narratives. We don't even know that we are doing it, but we look back and see that we are. We are helpless other than to pull ourselves into the zeitgeist. If you are unbalanced or a teenager, or both, as I was, I guess, I think you get drawn into the romance of that conversation. This is how I want to be part of that larger conversation. This is how we want to be a part of the larger world. How was John Hinkley trying to impress when he shot Ronald Reagan? Jodie Foster. When we are feeling small or insignificant we believe we are a part of a larger story line. Maybe we are. I really do not know. But I think ultimately that we are drawn to that as people. And films can become dangerous when they become a 'too on the nose' expression of that. It would be a lot different a book if I had seen Miracle Mile before I had tried to kill myself. Because Miracle Mile makes sense to me in a different way, after. OK, wait a minute, now I am watching this as a movie, it is almost surreal because I almost shouldn't be here. And in the first days after I tried to kill myself I truly believed that in a way I had done it. I succeeded. I'm dead right now - in my head. It makes no sense, a schizophrenic feeling inside my head. But you feel like this is all wrong. Like that Donnie Darko thing. Everything is wrong. I shouldn't be here. I am an interloper. And minutes I still feel like that. Whenever a great tragedy happens. You walk around the supermarket and cannot believe that nobody else knows. You are in the supermarket looking at people thinking, "How dare they buy chips!" There is one character that is so great in Men In Black 3. I'm not recommending the film, but there is remarkable character in it, an alien in there that is pan-dimensional, and he sees every possibility. And his dialogue is something like, "we are going to be OK, unless it is that one where the guy that falls down, and in that case we are all going to be dead in 16 seconds, UNLESS it is the one where... He sees every possibility and is completely out of time, the Vonnegut character from Slaugherhouse Five. He is out of time. Miracle Mile captures that in a really remarkable way. It is a movie that feels like grief. It feels like dislocation. That sort of mania of schizophrenia that happens right after. How does that movie begin to speak to me in a broader way about the entirety of the 1980s and the entirety of what we do. Of what you and I do. Writing about film, and talking about movies, and trying to convince someone that isn't entirely there that, "Hey Man! Death Proof touched parts of me almost nothing else has in about ten years."

KH: *Laughs* This is funny to me because I've spent an ungodly amount of time, you do not want to know, trying to convince people of the merits of Death Proof!

WC: And that even is easy because it is Tarantino. Try doing that with The Chronicles of Riddick. *Laughs*

KH: In Miracle Mile, you often start going to town with a symbolist or numerologist like glee. There is a playfulness in how signs and signifiers can play around inside your head. Using the apocalyptic tone of Miracle Mile as a vessel for humour.

WC: The movie is! It really is funny. I think that is an element that is lost too. I think I wrote about it in the book whenever I teach about His Girl Friday, there is a modern disconnect, where we are looking back at this relic which is 70-something years old. It is tempting to think that they didn't know any better and of course they are going to use offensive terms for black people, that you lose great swathes of commentary from older films when you give that time that easy break.

KH: A condescending, or self-superior sense that we are better now that we were then?

WC: I don't know. I don't think so. But when you look back at movie like Gunga Din for instance, did they know that it was offensive to compare this guy to an elephant? Did they know that? I think so. I think they are just being assholes. And I think when you look a His Girl Friday I think they are being smarter than we give credit. I think that they know that the terminology is antiquated and that they are using it anyway?

KH: Sullivan's Travels is very self aware. But then it is explicitly what that movie is on about. Certainly all of those Billy Wilder movies...People always say that Ace in the Hole was super-prescient of where things were going, but then they were probably always there.

WC: I think that one is super-reflective of what things had been forever. People just were not talking about it. When we think of Hearst creating a war so that he could sell more newspapers. We have been doing this crap forever and ever. When we talk about popular culture and where it is going, it is not like the great tragedies were selling out the coliseum in the golden age of Rome. What was selling out the coliseum was feeding christians to the lions. We've always been kind of derelict in our appreciation culture.

KH: You almost have to be in that era however to understand what you can get out of a time from it's trash. And I don't mean garbage, I mean Trash - something that is interesting. I wonder how many times we can get more out of that than the high-art of the era.

WC: The trash more often becomes the high-art in a way, because you are not necessarily trying to say something with it. You are not trying to be Stanley Kramer, but you are just throwing it out there. I doubt very much that Romero was trying to say anything about Christianity or race relations with Night of the Living Dead. But he did.

KH: Things are percolating in these movies, and come out unconsciously...Not necessarily deeply considered when these things were being made.

WC: You look at that era, and you look at things that were coming out. Rosemary's Baby was the same year, 1968, and they are both about this discomfort. How did Ozzie and Harriet produce Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix? That is the generation that disconnected. You get the Exorcist a few years later. Often if it is not intentional it is good, and if it is intentional, it is Guess Who's Coming To Dinner?

KH: Treacly, sentimental and hand-holding? You get at that with the Reagan era discussion. The "It's a new morning in America" stuff. Miracle Mile is the complete opposite answer to that movie. There is a part of me when I watch that film, whether it was the first time I watched it, or many, many times later that there was part of me that thinks I wish they didn't show that the nuclear bombs going off. They go far enough that it is 99.9% unambiguous, but in a way, I kind of wish that Miracle Mile would have been a virus of an idea spreading. The Pontypool, Snow Crash idea there are so many things that can spread and be a self-fulfilling prophecy. All the ways that Miracle Mile circles in on itself. It's interesting that Steve De Jarnatt decided to come right out and say that WWIII really was happing.

WC: I think originally it was even more on the nose. I think he wanted the budget to show mushroom clouds and devastation. He wanted the last scene in the film to be two diamonds on a dark screen that roll back. It is hard to climb into his mind. I only talked to him a couple of times when writing the book. But for me, that movie, the first time I saw it, I still haven't seen it on 35mm. I've never seen it projected. When I watched it on DVD for this book, I realized that it was probably the first time I saw it in that format. I had always been watching it on VHS. And when I started writing this book and going through the first couple drafts, I realized I was writing a lot of it from memory. And when I went back through the DVD and started watching it frame-by-frame, I realized how many mistakes I was making.

KH: Your memory of the movie vs. the reality of the movie.

WC: Exactly, and everything that is mixed up inside your head. You were mentioning earlier about numerology, and these wild connections here and there. *Laughs* But I was not trying to be funny, but more how I was trying to demonstrate how I come at this movie. It didn't stand by itself anymore. Everything is connected to something else. You mentioned in your email when I was talking about Hamlet, but using an example from Macbeth. I don't know. It has become, I hate to admit, that I'm more familiar with Robin Williams doing the impression with it in Good Morning Vietnam. It is a terrible thing, but I start to realize that we are all these collections of signs and signifiers. That something happens. Something pops. And you think, I saw that guy stab Janet Leigh in Psycho 25 times and the dagger going into her flesh and the intestines coming out. I saw all that. But we never see anything that is outside of our head. Everything becomes part of the conversation. When you write in long form, you feel like, all I'm doing is connecting all these bridges in my head, and trying to be honest about much I'm not paying attention.

KH: In the book you talk about Miracle Mile being an Anti-Romantic elements of the movie: That Mare Winningham's responses to his comments. When she recognizes something he loves. She doesn't know it and really, she doesn't even care. She's being polite on a first date. And it is a pitfall in how so many relationships fail is that you actually project a little connection and you blow it way out of proportion. It seems that is all Anthony Edwards does during the film. He is even quite condescending about it to her, he will not tell her anything. When you say this hearkens back to the 50s, it perhaps goes back to that worst male dominated aspects of the past.

WC: I love how the film comments on that in a way. In the way that she doesn't respond to his showboating. When he starts to do his trombone thing and everyone is kind of irritated by him because he is showing off. And the hold guy John Agar loves it. But she is uncomfortable with it. And later when he is pushing her around in a shopping cart. Here we go. This is very, very essential to their relationship. He has decided. All she has decided is that she is going to have sex with him in a couple days. He has decided that she is THE ONE. And the fallacy of that.

KH: Right, the wonderful moment where she wants to go with her parents for breakfast, when she sees them back together and doesn't know why, the apocalypse that she is not aware of happening yet.

WC: Exactly, he will not tell her because he thinks she is too delicate to make any decisions. Every time I watch the movie, I like Anthony Edwards' character less.

KH: Yet it is a really great performance by Edwards. The scene in the department store by the escalator, as Winningham recognizes that Edwards has told Wilson a completely different set of reasons to panic, and you wonder if she thinks for just a second, whether or not her boyfriend is a complete psycho. Telling everyone a different story. The movie pulls away from that, but it is there for a brief instance.

WC: It is interesting about her too. She says weirds stuff about her parents. Things like nobody loves each other than they have, ever. There is an implication that she likes to tell stories too, to impose things as well. Is this going to be the basis of their relationship? Self-aggrandizement? That I'm the princess and he is the prince. He's already there. Is she beginning that process as well? It is a sneakily great performance by her as well. Hidden underneath her bad wardrobe and hair. You don't take her seriously the first few times you see the movie, you've kind of want to treat her that way. For me, I feel like, she's not a child, she is kind of sophisticated. She is a little wonky, but then she is kind of beat up. You know the second time you watch Punch Drunk Love, you realize, wait a minute! Emily Watson is just as crazy as Adam Sandler.

KH: Well you do get some Breaking the Waves baggage with Watson.

WC: You do.

KH: Miracle Mile such great use of character actors. One of the best, really, until HBO came along and made that their business model. This one movie, you point out in the book how deep that goes, such as the woman in Johnie's Coffee shop who has no lines, but was played by the actress who did Smurfette's voice on the cartoon for years. Or the actress playing Mare Winningham's mom is the woman under stairs in Sam Raimi's Evil Dead II. And then folks like Kurt Fuller and Denise Crosby and the desk Sergeant in Robocop, Robert Doqui. The use of all these character actors is so organi - they are all doing kind of what they do, their types. How many waitresses has O-Lan Jones played? But her performance in Miracle Mile is the best one. It is smart in how it uses its vast collection of character actors.

WC: There is a real Tarantino quality to it. I think De Jarnatt understands the way these actors tick, and that he put them in the right roles for it. Even someone like Mykelti Williamson who is Bubba now, forever. He is really an interesting presence in that movie, for the racial aspect that he brings, but also the way that he talks. "Hey Man! I got Nuthin'!" There is something that De Jarnatt brings out in all these actors. I don't know if Anthony Edwards has ever been better. Good enough that he asked De Jarnatt to come and do a couple episodes of ER personally. I think there is something he understood. With Mare Winningham. I feel that if you asked him, he wouldn't be able to articulate it, but he does have a real sense of these people. His student film, something called Tanzania with Eddie Constantine, of Alphaville. It's really interesting and it captures this really cipher quality of Constantine. I'm not sure that Constantine is used in the right way, but De Jarnatt did. I really search for hints of that in Cherry 2000. I really want that movie to be better.

KH: It is a fun cast in that one. That and Albery Pyun's Nemesis are the only two films that put Tim Thomerson and Brion James together. One of the great lost opportunities, I think would be to see a zero budget yet badass buddy flick featuring these to guys.

WC: Yea, for all the crimes of Cherry 2000 the supporting cast is not one of them. I think what is vital about Miracle Mile, is that everyone works in it. Danny De La Paz, who plays the transvestite, works, he has one scene. Rapheal Sbarge, the voice on the other end of the phone, works. He is doing all this voice work for Mass Effect and the video game industry. De Jarnatt had this thing about being able to figure out who was good at what. He might be saying, "I don't want you to be different, I want you to be that. More." Like John Travolta in Pulp Fiction.

KH: There is a circular nature of the film. It starts at the museum and ends at the museum. It 'really' starts at Johnie's coffee shop and comes back around to Johnie's coffee shop. There is this kind of loops in loops. The Big bang that killed the dinosaurs, and then the big bang that kills them in the movie. But it doesn't do it with the actors, in that when they exit the story, with only a few exceptions, they are gone for good. There is kind of a restraint to going full on fever-dream in the manner.

WC: I think it walks the line well. I think it is a tight story. I think he had some real thematic repetitive resonance to it, like any good fairy tale should. But it does walk that line. There are so many vivid moments and vivid characters. I always wonder if Jeannette Goldstein and her partner made it to the arctic and what is going on out there. You imagine Vasquez and Lieutenant Yar starting a new colony of humanity up there. There is something interesting about how well the film is structured but seems larger than what it is.

KH: When Brian Thompson, the heli pilot, comes back in the chopper but he is covered in blood as if some real shit went down at the airport...none of which we actually see...

WC: And where is the boyfriend, Leslie that he wanted to save?

KH: Miracle Mile is the apocalyptic romance. That wonderful superman speech, it's better than David Carradine's speech in Kill Bill. The last line of dialogue in the Miracle Mile, and it is that romantic thing, but the movie is also hyper-aware of how not-romantic it is. It is an intelligent contradiction? It kind of wants to have it's cake and eat it too.

WC: I agree. I am really taken with the Superman mythology anyway. It speaks to the father-son thing in a really direct way. The way it really understands meta-textually I guess, about the romance and the nostalgia in one moment. Brilliant. Absolutely brilliant, almost heart-breaking. It cannot be more...I'm not going to sit here and tell you (no one would listen anyway!) that this should have been on the same Sight & Sound list as Vertigo. But for me it is important because Miracle Mile is not about what it is about, necessarily. It is about everything. And at the same time, the way that I love my wife. That is what it is about. I is about what I think about my child and that is what it is about.

KH: But it also a lie! The horror and the excellence of that is that it is both romantic and a lie.

WC: And he never stops lying. He's a real bastard.

KH: Not the qualities you want to trump it a hero. Perhaps a risk taken?

WC: I was really fascinated that De Jarnatt wanted Gene Hackman, as an older gentleman going back to find his ex-wife. It is an idea that I really rejected for a long time after he told me. I don't see that, because I like the young thing. I like it so much. But then I thought, well, he's right. The qualities you identified, the 1970s era paranoia and all that. Wouldn't it have been wonderful to see Gene Hackman do this, and not be taken seriously, and have this breakdown.

KH: What Kubrick does with Eyes Wide Shut with Tom Cruise? That movie is a masterpiece, but there is also sense that Kubrick just wants to undermine Tom Cruise's star image with that movie as well. To emasculate him. To make him an impotent dickweed. There is lots of other thing going on in Eyes Wide Shut, but that one is certainly amusing.

WC: And Kubrick, like so many great filmmakers, was RIGHT! Tom Cruise is now living THAT.

KH: *Laughs* I never thought about that, but we are living Cruises personal life as that long dark night!

WC: And I wonder if Eyes Wide Shut hasn't gotten got that critical revision for proving itself absolutely right!

KH: As a harbinger of what has happened?

WC: Yes, in the sense that WE didn't know, but Kubrick DID! He got to spend time with the guy, and maybe that is all it takes. I wonder if movies don't become, like The River Wild, don't get revised because it turns out they were right. Movies like Idiocracy that have a huge cult following, not because it is funny (it is) but because it is right. You are dead on correct when you talk about these things. Manchurian Candidate almost seems like a documentary. At the time, it was science fiction. We look at it now, and think how quaint!

KH: So said right at the beginning that you don't know if you have another of these monographs in you, but right in the text, you mention Vampire's Kiss. Another 80s signature movie, with a signature crazy Nic Cage performance. And like Miracle Mile, it is not well known, but still tends to blow people away with how good it is. And in the Ratatouille Anton-Ego sense, its worth unearthing these types of movies is the good work of a film writer. Do you have another one in you.

WC: I'll answer this in this way. Miracle Miracle was written just as we were about to scatter my father's ashes, nine years after his death. And we did that a couple weeks back. Knowing that was coming up. And having just watched Red Cliff, there is a character in there, Zhou You is his name, he is sort of the Chinese equivalent of Odysseus. He is the main character, and he is the smartest, and the most virtuous. I was named after him, but I didn't know that. When I was growing up, this is a Chinese thing, or maybe just an abusive thing, but they told me my name was a joke. That it meant fool, and that they named me that so that the gods wouldn't think I was arrogant. Every time I was introduced to Chinese people I would cringe and I still have hang-ups about my own people. Because I believed that they were laughing at me. That they were being told a certain thing. And that really wasn't the case. It was the opposite of that. But I didn't know that until I watched Red Cliff. Every time they said his name over the course of a six hour film, I cried. I had never heard my name - I never thought that I'd heard my name - spoken with reverence and I didn't realize how deep that it affected me. So that was on thing. And then I watched Tree of Life a few months later. And the talking about the father, and the way men are with kids. And the way that Brad Pitt says to the kid. "Hey! Come Here!" and the kid is terrified, and then he gives him a hug. And I was not prepared to see that right then. And between those two things and knowing that that anniversary is coming up, and reading Jonathan Lethem's book [A similar style monograph on They Live.] I needed to do to this for my sake, and for the sake of my kids and I needed to simply get over it. Some people have whiskey, I have movies. Vanishing inside them for a while and then coming out talking about it. Why am I attracted with father figures in movies, and what is it about writing about movies for over a decade, and what is Miracle Mile begins to uncover for me. And I wrote it in two days. I just needed to get it out, and I don't want to make it mystical or Dr. Phil, but I was a wreck for the first time in a long time. Then the editing process was one of avoidance. Bill would send me things, and the email would sit in the inbox for a couple days. I would avoid looking at it. And towards the end, he said to me, "Just print it out. Look at it in a different medium." And I did. I looked at it for easily a month. It just sat on my desk. I finally went through it and red-marked it all. Then I lost it. Then I went and printed it out again, and it was another two months after that. The editing process was avoidance and denial! It was like, I've done it now, I don't want to look at it. I'm done with this. I might have another one in me, but I don't have the triggers yet to do it. If I did do it again, it would be afraid that it would be not personal. That it would be lesser. This one wanted to be born and maybe the other ones would be nursemaided. I feel like, aside from something stuck in my throat, I kind of do this sort of stuff every day, I'm working on a big piece of the four Lethal Weapon films right now and that I am getting a lot of stuff taken care of with that. Maybe less of a personal way. I have an outlet for the every day kind of stuff. I'm not sure there are many more films like Miracle Mile in my history. That I need to talk about. I love Vampire's Kiss. I love that the main character is a rapist and pretend vampire who cannot afford the real teeth.

KH: Another weird connection is that, I believe, in Vampire's Kiss there is an echo of a shot in Miracle Mile. When Anthony Edwards sees two headlamps of a car coming at him, and it turns out to be two motorcyclists. This shot is done even more cinematically, but to the same purpose in Vampire's Kiss.

WC: And if that is the case, I honestly do not remember, but doesn't that speak to the idea of imaginary menaces, what is a real threat of what is just a paranoid threat. When you have the same image recurring, that is fascinating. There is something true to that period, and I hope that is what it is.