Series Preview: Nina Menkes Retro at New York's Anthology Film Archives

Whether such an approach would dazzle you with its originality of presentation or simply make you impatiently hungry for the meal you ordered, might reflect your reaction to Menkes' films. Indeed, they probably include just enough narrative to irritate avant-garde purists and just little enough to drive mainstream audiences batty -- which is precisely what I like about them. With a challenging sense of pacing that gradually wins you over to the point where pacing seems like a pedestrian concern, Menkes' work never quite induces the "trance" of some experimental films, but rather evokes a meditative state of mind. And since most, if not all, of her films are concerned with matters spiritual, that seems only right.

The Anthology's March 9-March 16 retrospective on Menkes (with the filmmaker in attendance) should help make these hard-to-see titles a bit more accessible to New Yorkers, if only in terms of actually seeing them, not "getting" them. If you're unfamiliar with these films, below is my quick take on a portion of the lineup -- although once you've seen them, I'm sure the meaning you construct will be just as valid, or more valid, than mine. That's not a knock on Menkes but rather an acknowledgement of what appears to be one of her guiding principles: the co-authorship of a film with the audience, similar to how gazing at a Pointillist work makes all the dots coalesce in a manner that, strictly speaking, they simply don't on the canvas alone.

The Great Sadness of Zohara (1983): At a runtime of 40 minutes, this is an allegorical gem in novella form. Menkes begins her memorable collaboration with her actor-sister Tinka, as the latter treks from Israel to North Africa, and from conformity to inner peace. An epic pilgrimage in 16 mm.

Magdalena Viraga (1986): Although probably my least favorite of those titles in the lineup that I've seen, it's still a terrific example of the Menkes aesthetic. Stunningly recursive, with events played, re-played, and re-replayed, this prostitute-kills-john exercise showcases plenty of monotonous sex, and then splashes of blood, and then some more sex, and then -- well, you get the idea. My chief gripe? Rather than letting the innate poeticism of the images and their editing-together suffice, we get feminist poetry intoned directly at us. That might sound interesting in theory, but in practice it shows up like this riff on Anne Sexton: "Your penis, sewn on you like a medal / all life and feeling departed from it... / soon you will have no voice / so sing now / now." Oh, and I'm guessing at the line breaks, by the way. Also in 16 mm.

Queen of Diamonds (1991): There are some rough spots in terms of acting, but all in all, another extraordinary piece of filmmaking. A blackjack dealer takes care of a dying man in her spare time; next door, a much younger man regularly beats his fiance, and makes too much noise doing it. And that's about it. The centerpiece, if one can call it that, is an extended dialogue-less sequence in which casino-goers show up, play a few hands, and are then replaced by others after a cut-in to the dealer drawing a new card. But then we see the players from earlier gradually reappear, so did they wander back or is this just the same footage inserted later on? Never has a film so subtly captured the timeless feeling of a casino floor -- or the rote banality of working for a living. In 35 mm.

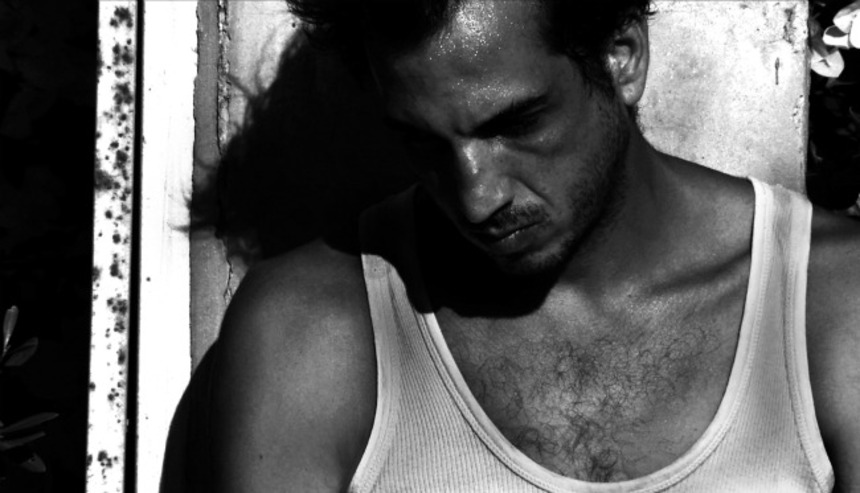

Dissolution (2010): Menkes's latest feature, pictured above and shot in noir-ish black-and-white HD, gets an actual (and well-deserved) theatrical run during this retro. Sporting several Menkes trademarks -- characters run away from the camera, and yet when they stay still the camera seems afraid to approach them -- but wed expertly to a Dostoyevskian character study, Dissolution is quietly thrilling. Yes, there's a murder in this Tel Aviv-set story, but please, please don't expect an actual noir. Instead, settle in for one of the more intense depictions of anomie you're likely to see on the screen this year, or next. In fact, be prepared to be stared at by several characters in a kind of silent reproach for attempting to be entertained by the proceedings. As for lead David "Didi" Fire, his remarkable work really doesn't seem like a performance at all. One can only wish that he and Menkes will make additional films together.

(The featured still from DISSOLUTION is copyright Nina Menkes/MenkesFilm and is used by permission.)

Do you feel this content is inappropriate or infringes upon your rights? Click here to report it, or see our DMCA policy.

(1)-thumb-80x80-93563.jpg)