An Interview with PONTYPOOL author Tony Burgess

During the hubbub and all around busy-ness of this years Toronto International Film Festival, there was one film that I found the perfect combination of smart, inventive and entertaining. I liked it so much that I managed to two screenings of it, a rarity (actually a first) during the scheduling and logistic complexity of that festival. Perhaps, the worlds first semiotic zombie flick, yet its less than usual storytelling style actually goes back to old-school horror filmmaking, (in that there is much more implicit than explicit) and as a bonus is in no short supply of regional (Canadian) flair. The sly reference to Herk Harvey's Carnival of Souls (and for that matter, George Romero's Night of the Living Dead) cannot be overlooked. I believe the film is ready to have some cult-love bestowed upon it, a la Ginger Snaps, Cube and Black Christmas (or more maybe more appropriately Deathdream). After hogging the Q&A during the first screening and still asking questions during the second (yes, the film is more textured and just as fun the second time around), why not hit up a few of the guilty parties with a more (or less) formal Q&A.

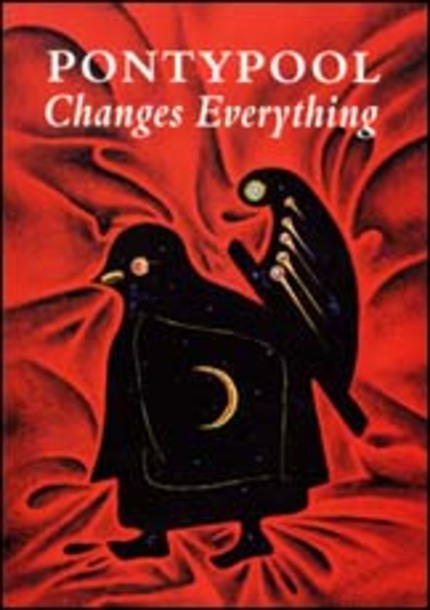

Tony Burgess is the author of the novel ("Pontypool Changes Everything") on which the film, Pontypool, was based. He also wrote the screenplay and appears in a tiny cameo in the film to boot (or get punted as the case may be). We talk about the nature of the film and language, and lest folks be worried about the whole *spoiler* aspect of things, perhaps Tony's own words sum up talking about Pontypool without spoiling things, "We had to satisfy that it is most certainly happening and it just might not be so."

What were the challenges in drafting the screenplay from your own novel? What to keep, what to throw away, I understand there are large differences here.

The key to the translation wasn't about extracting the novel's story elements, character, plot etc. The novel is an unstable document and, for me, the real challenge was how to translate that instability and uncertainty into a screenplay. Screenplays that are uncertain and unstable don't and probably shouldn't get made because film, more so than books, absolutely depend on the veracity of the image. If you don't believe or understand what you are seeing you very quickly lose interest. The events in a film have to be happening. So if the first challenge was to translate instability and uncertainty, (and I mean primal ontological uncertainty) then the second challenge was to conceal that in the guts of the story...to have you feel it in a `sinking feeling' kind of way as opposed to getting it in a literary way. This is the central challenge of not only the script, but of the whole production. Especially the actor's choices. There are a number of elements from the novel that remain in this version and, given that the novel was published in a state of being `unfinishable', the film as an added chapter fits perfectly.

Your books are in a trilogy (there have been some rumblings about a Pontypool film trilogy.) Would you be interested in adapting all of the books into screenplays, and how would things be handled in a part 2 and part 3?

Well, yeah. I'd love to adapt the others. I feel now that I know the author a little better. Ponty2 and Ponty3 are, like the first, new chapters to an unfinished novel. Ponty2 takes place nearly simultaneous with the first film, so it isn't a prequel or a sequel more a kind of equal, I suppose. Ponty2 goes out into the world where this is all happening. We hear the first film on the radio throughout Ponty2, but now we get to see what the fuck happened to this town that day. On the surface this sounds like we're giving up on the unique controlling principles of the first film, for the sake of making a more conventional genre piece but, in fact, Ponty2 is a version of the film we tried to get made for years and were told it was too perverse. In Ponty2 we let some of those instabilities and uncertainties up for air. Blood spray, gut flapping and auto-decapitation are the order of the day.

You made it through the film without using the Z word.

The Z word is all over the novel which makes that word its subject, but in zombie films, for the most part, it is an audience word. Characters in zombie films don't typically say `I think that's a zombie', audience members do. So even if we weren't being evasive about our genre (Ooops!) I don't think we'd be using the Z word. But clearly we don't or can't stop the audience from using it. Hordes of bloody and babbling automatons! C'mon, man, they're not the fuckin’ care bears.

There are not very many films which use language as the key ingredient plot-wise, what was the inspiration behind language/communication/understanding as the driver for infection?

When I had just finished my first book, The Hellmouths of Bewdley my publisher sent me out to get an author photo for the cover. My wife and I drove out to Bewldey thinking a picture of me standing on a dock on Rice Lake would be perfect...turned out the sun went down and we ended up pulling over to the side of the road and taking a pic in some town along the way. That was Pontypool. I had some pressure on me at the time to write a second book so I said,"I owe Pontypool a book.' When I finally saw the picture a number of things struck me. The picture reminded me of the photographic illustrations in Andre Breton's Nadja and the surrealist photographs of surrealists sleeping (Hans Richter, I think, or Man Ray). Nadja because they are pictures of a person not seen in the image (Pontypool), so that one thing I thought was that the book Pontypool would have to be a dream (the inside of the sleeping poet - Bewdley) and it would have to involve the effects of an absolute misreading or rogue signifier (ponTYPOool is Bewdley...) anyhow, I had just finished a degree in semiotics so I had all this pent up theory shit in my head (Julia Kriseva's Black Sun in particular) but what I really wanted and what I have always written and still do is a book about the sudden and convulsive end of the world that runs in two equal and opposite directions: It is most certainly happening AND it's not necessarily so. The language virus just fell in as an idea that allowed me to do these things. It wasn't, ultimately, French semioticians (or Laurie Anderson/William Burroughs) that helped me build it but neo-platonic grammarians and occult memory theorists from the early modern period. (What?!!?) Petrus Ramus influence on Marlowe (the final scenes in the film are modeled on Marlowe's final scene in Faust - oh my god, this sounds pretentious, but, whatever, you do what you do) and Giordano Bruno, Fuccini and others who where convinced that rhetoric had the ability to change everything. That if words were absorbed into places and spoken in a certain order by a person who felt this way or that and had ordered their recent memory properly then by uttering the simplest of words or phrases they and the world could be altered essentially. I needed ideas that contained insane ambitions because, basically, it had to work as a horror story, it had to work as if thought up by mad science (“It's Alive!") I have always thought (wrongly) that the real students of Un Chien Andalou were the makers of Phantasm, not David Lynch. In the film the other obvious influence was HP Lovecraft. The great unnamable closing in. Uncontainable. Unknowable. And, ultimately, us.

Also, it seems that at one point (particularly the opening monologue that it is going to be a particular turn of phrase that sets things off, perhaps a phrase that has never been uttered aloud before, but then the story goes a bit of a different direction), but veers off in a different direction.

I was always wary of the film getting hung up on the technical rules of its own concept. Bruce and I fought with people for years over this. We wanted the virus to be unknowable. And, we wanted to experience this in the people who were being overtaken by these events. We wanted to stay very tightly tied to the subjective experience and if we gave too much story to the objective life of the virus it wouldn't work. We had to satisfy that it is most certainly happening and it just might not be so. Anyway, once you start getting too elaborate with the way of the virus then I think you take something away from the audience's ability to speculate as wildly as they want.

At one point this film was to be a radio play for CBC, then at a point it was to be filmed entirely in the DJ booth, the shot never leaving Grant Mazzy's face - your idea I believe. How did the project evolve into the structure of a more conventional film?

The idea of never leaving Grant's face served a whole lot of things. As mentioned above it secured the audience's subjective trust that this was happening. It also unified a story that is threatening to fly apart. (Sunny Aristotelian unities in service of mad neo-Platonic nightmares.) It also helped us develop this: we wanted a story that was nearly unbelievable to be experienced by someone who almost doesn't believe it. It's a tricky line to walk, but it's a counter to the way people in horror films so quickly believe or understand crazy things in order to get to the meat of the film, which is to deal with it. We wanted to stop before `deal with it' and make that an impossible thing to do. I also thought that if we accept this challenge (one place, one person, one time) and work very hard to make it work then we might find our story achieving things we couldn't anticipate. The project's frame got a little bigger but the springs stayed coiled the same way. Everyone on the film seemed to understand this and became watch dogs for violations. The editor Jeremy Munz was very keen on discovering places where we knew or saw things outside of the emotional atmosphere of the room. Miro, the cinematographer, too, was very smart about knowing how and where the film can and cannot look at itself. The actors where amazingly instinctive at getting the right bends and emotional drops to keep us feeling close to something we couldn't believe or understand.

How do you go about balancing ideas, horror and humour in the film. Was it a conscious decision or just how the story evolved.

To me the whole thing should be hilarious and horrifying. We had signs on set saying `Scary Not Funny' because we wanted to make sure one or the other didn't break out and control things. If it's funny then I'm happy. It's scary then I'm happy. If you're laughing and frightened then I'm really happy.

There is some commentary on the news and media setting the tone of the conversation. This amusingly leads into a jab or two at Canadian Identity. How's your French and should we all be bilingual?

My French is non-existent. I'd love to be bi-lingual.

Do you sing or have you sung professionally before?

Oh no, sir. I do not sing professionally. I did, however, get caught up in small town musical theatre for a while and the scene in the film is absolutely an accurate portrayal of a trip I took with the cast of the King and I to a local radio station. So the scene in the film goes to small town authenticity.

Is language a virus in the human organism, or are humans the virus and language the organism?

Is that a Zen Koan or something?